Curing Concrete: How we used to do it

The concept of curing really has not changed over the years, although 100 years ago some unusual methods were used.

The American Concrete Institute (ACI) defines curing as an action taken to maintain moisture and temperature in a freshly placed cementitious mixture…so that the potential properties of the mixture may develop. The definition from 1910 was a little more direct on what you should do. “Green concrete should not be exposed to the sun until after it has been allowed to set for 5-6 days. Each day during that period the concrete should be wet down by sprinkling water on it both in the morning and the afternoon”.

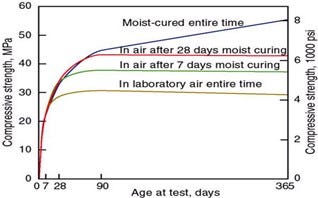

Research has shown that concrete needs to be cured. Concrete that has not received curing can lose over 40% of the strength it could have achieved with a 7-day moist cure. Research has also shown that concrete cures best with temperatures between 40°F and 90°F. Modern building codes state that concrete should be maintained in a moist condition above 50°F for 7 days. The inspector is required to document what the contractor is doing to protect the concrete when the air temperatures are below 40°F or above 95°F.

Over the years, several methods have been used to achieve good curing. All of these were intended to maintain adequate temperature and moisture in the concrete. Some of these methods are still used today, others were either discarded, modified, or have limited use.

Manure

On the farm, manure was considered to be the best curing method and farmers were encouraged to use it to cure their concrete. Most farms had a manure pile, a steady supply of manure, and it was free. Manure would keep moisture in the concrete and in cold weather provide insulation to keep the concrete warm. The reference to this curing procedure warns that the concrete would be stained by the manure so it should not be used when appearance was important. This method never caught on and I cannot find any data supporting the statement that this was the best curing method.

Soils or Sand

A thick layer of wet soil or sand was recommended to be placed on the concrete after the finishing was completed. This method is still used today however I can’t find a definition of how thick the layer needs to be. ACI states that the sand should be thick enough to hold water uniformly over the entire surface. I got involved on one project where the contractor placed concrete right before freezing weather occurred. To protect the concrete, they put a thin layer of wet sand on the concrete. It did keep the moisture in the concrete however the top surface of the concrete still froze and had to be removed.

Straw or Hay

Early references state that 12 inches of wet straw would provide adequate curing. The straw would need to be kept wet plus it would need to be covered so that it would not blow away. (One reference states that straw with manure works best). These references also caution that the concrete could also be stained due to the wet straw. ACI still includes this method of curing in its documents, however states that only 6 inches of straw is needed. It also warns that straw and hay are a fire hazard. It does not recommend straw or hay be used to protect the concrete in cold weather. For these reasons, straw is seldom used to cure concrete, but in countries with limited resources it is still sometimes used.

Burlap

This was a common method of curing concrete slabs. The burlap must be kept wet thus the requirement as stated in 1910 was to sprinkle the concrete/burlap two times a day. This procedure will probably work in many areas, however in low humidity, this will likely not provide adequate curing.

When I first went to Saudi Arabia, they used burlap and a sprinkling can to wet the burlap twice a day. Unfortunately the burlap remained wet for only about 15 minutes (temperatures routinely exceeded 110°F with humidity below 5%) ,thus the concrete was not receiving an adequate cure.

One method used to keep the burlap wet is to put a continuous sprinkler on the burlap. Although this system will provide an adequate cure for the concrete, the contractor now has to worry about the water run-off and how to keep the water on the job site. The ACI Flatwork Finisher’s Workbook also warns that when using burlap with sprinklers, the runoff could saturate the base/subbase/subgrade and undermine the slab or cause problems with moisture sensitive flooring. For these reasons, burlap curing is typically not used on larger projects.

Canvas, Heavy Paper, Old Carpets

All of these materials were used to keep the moisture in the concrete and in cold weather to help maintain a good curing temperature. The covering could be reused provided they were given a chance to dry out between use. The contractor was warned that the covering could mildew if not properly dried.

Flooding/Covering with Water

Covering the concrete surface with water was considered one of the best curing methods unless there is freezing weather. This method certainly keeps the moisture in the concrete and provides additional water as well. One way of achieving this curing method is to build an earthen dike and form a pond on the concrete surface. This method is very labor intensive and requires regular inspection to make sure the dikes are not breached and that the water has not evaporated.

The concept of curing really has not changed over the years. Many contractors will still use coverings on concrete surfaces. Today we would use plastic sheets rather than old carpets. Some mixture designs with very low water-cement ratios require water curing because the extra water is needed to complete the chemical reaction between water and cement (hydration).

We have also developed curing compounds that put a coating on the concrete to keep the moisture in the concrete. In cold weather, we will typically use insulating blankets or heating units to hold the heat in the concrete.

All of the methods described above are intended to protect the concrete so that it can achieve its maximum potential properties. A common statement that I use in my certification classes to drive home the importance of curing is “When it dries, it dies!”. If we keep that concept in mind, we can achieve the potential properties of our concrete by providing adequate curing.

Luke M. Snell is a concrete historian and Emeritus Professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like